I have repeatedly mentioned here on this blog that I am not a fan of Applied Behavioral Analysis (link). I have stated that I hold these objections for various reasons:

- I consider ABA to be compliance training and I have grave concerns regarding the long-term consequences of teaching disabled youth that compliance with instructions from people in authority is more important than their own instincts (link).

- I believe that ignoring a child’s thought processes and cognitive abilities is never appropriate, and doing precisely this is an essential component of ABA (link).

- I reject the assumption that S-R associations and behavioral outputs are predictable and can be made to be predictable by careful application of reinforcements and punishments

- I also have given another reason that I have never fleshed out: ABA simply does not work.

I will explain this point in detail in this post.

Feel free to peruse an earlier post for a primer on reinforcement if you do not have a solid grasp on what I mean by positive reinforcement and negative punishment.

A BRIEF FORAY INTO REINFORCEMENT SCHEDULES

Continuous Schedule. A special case of reinforcement used a lot in educational settings and with very small children:

-

Continuous Schedule of Reinforcement (CRF Schedule) – Every single target response = reinforcement

Partial Reinforcement / Ratio Schedules refer to a situation wherein every Nth target response is reinforced. This comes in two flavors:

-

Fixed Ratio Schedule – The number of responses to get a reinforcement does not change (e.g., always 5 target responses = reinforcement)

- Variable Ratio Schedule – The number of responses required to get a reinforcement is unpredictable (e.g., it can take between 1-8 target responses to contact reinforcement, with a mean number of 5 target responses required)

Interval Schedules refer to a situation wherein the first response after a certain time interval has elapsed is reinforced.

-

Fixed Interval Schedule – The time interval after which the first target response is rewarded does not change (e.g., always after a 5-minute time period the first target response = reinforcement)

-

Variable Interval Schedule – The time interval after which the first response is rewarded does not change (e.g., always after an unpredictable 1-8 minute time period (mean of 5 minutes) the first target response = reinforcement)

B.F. Skinner and colleagues determined that the Variable Ratio schedule is the most resistant to extinction – meaning it is extremely difficult to get rid of a learned behavior if acquired using this schedule.

He also reported that the Fixed Interval schedule was the most susceptible to extinction. More so, at times extinction could happen spontaneously or after only a few missed reinforcements – meaning even a well-learned behavior acquired with this schedule is easily forgotten.

Here is a free link to the entire book by Ferster and Skinner published in 1957. This is the book wherein they describe in detail all the reinforcement schedules.

CHARACTERISTICS OF REINFORCEMENT SCHEDULES

Here are interesting facts regarding reinforcement schedules.

From Wikipedia (emphasis mine):

- Fixed ratio: activity slows after reinforcer is delivered, then response rates increase until the next reinforcer delivery (post-reinforcement pause).

- Variable ratio: rapid, steady rate of responding; most resistant to extinction.

- Fixed interval: responding increases towards the end of the interval; poor resistance to extinction.

- Variable interval: steady activity results, good resistance to extinction.

- Ratio schedules produce higher rates of responding than interval schedules, when the rates of reinforcement are otherwise similar.

- Variable schedules produce higher rates and greater resistance to extinction than most fixed schedules. This is also known as the Partial Reinforcement Extinction Effect (PREE).

- The variable ratio schedule produces both the highest rate of responding and the greatest resistance to extinction (for example, the behavior of gamblers at slot machines).

- Fixed schedules produce “post-reinforcement pauses” (PRP), where responses will briefly cease immediately following reinforcement, though the pause is a function of the upcoming response requirement rather than the prior reinforcement.

- The PRP of a fixed interval schedule is frequently followed by a “scallop-shaped” accelerating rate of response, while fixed ratio schedules produce a more “angular” response.

- Fixed interval scallop: the pattern of responding that develops with fixed interval reinforcement schedule, performance on a fixed interval reflects subject’s accuracy in telling time.

- Organisms whose schedules of reinforcement are “thinned” (that is, requiring more responses or a greater wait before reinforcement) may experience “ratio strain” if thinned too quickly. This produces behavior similar to that seen during extinction.

- Ratio strain: the disruption of responding that occurs when a fixed ratio response requirement is increased too rapidly.

- Ratio run: high and steady rate of responding that completes each ratio requirement. Usually higher ratio requirement causes longer post-reinforcement pauses to occur.

- Partial reinforcement schedules are more resistant to extinction than continuous reinforcement schedules.

- Ratio schedules are more resistant than interval schedules and variable schedules more resistant than fixed ones.

- Momentary changes in reinforcement value lead to dynamic changes in behavior

WHAT DO THESE RATIO SCHEDULES MEAN

In the context of my criticism of ABA, I will address a specific and almost completely overlooked weakness in how reinforcement is scheduled that Skinner actually discussed at great length, but gets routinely overlooked today.

OPERANT CONDITIONING

If we are training a rat to make a certain response to receive a reinforcement, we use a CRF schedule. Every single correct response is met with positive reinforcement. This works amazingly, so long as we maintain the 100% reinforcement contingency and make the rewards small enough that the rat does not satiate.

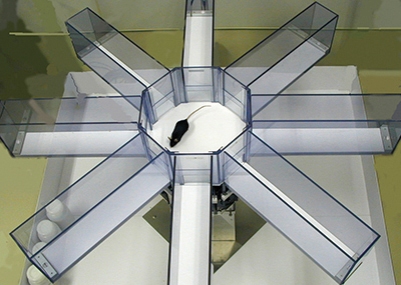

An undergraduate student was training a rat on a delay-nonmatch to sample task on an 8 arm maze. The student would raise 1 arm, let the rat run to the end and consume a ¼ froot loop and run back into the center. After a 10-second break, the rat was given a choice between the arm it just went down or a chance to go down the arm they have not gone down before. The rat was supposed to choose the new one to get a ½ froot loop.

This was going great, the rats were learning very rapidly and we were trying to get them to 95% correct responding before the experimental phase. However, one day the student working for me was having a bad day and forgot to reload all the arms of the 8-arm maze. Midway through each daily training session we had to reload all the arms on the maze so the rat could complete 8, rather than just 4 trials).

This means that the second half of each session, the rats did not get reinforced for their correct choices. But before this and in the subsequent days the reinforcement was 100%.

Can you guess what happened to his 4 rats’ behavior?

They stopped performing the task correctly. They forgot what they were being asked to do. They just started running down random arms. They went from 75% to around 50% correct and did not show improvement over the next week.

The student was at a loss. He came to speak to me, and I was also confused until I saw a specific oddity in the data sheets and asked what happened that day the student forgot to reload the maze. At that point he realized what had happened as well.

What had happened was that the reinforced response went straight to extinction. It only took 4 trials in a single day. We were never able to get those rats to learn the simple task.

One. Small. Seemingly insignificant. Mistake. That was all it took.

CLASSICAL CONDITIONING EXAMPLE

I was performing a fear conditioning experiment with a rat. This was basically the experiments that Ivar Lovaas based his positive punishments on for his early version of ABA/behavior modification. There was an 8-second tone followed by 2 seconds of tone+shock in a cage, followed by 50 seconds of silence.

After 10 trials the rat was removed and put back in their home cage overnight. 24 hours later these rats were given a test the next day wherein the tone was played continuously for 2 min in a completely different room and the time for the rat to demonstrate it was no longer scared of the tone was recorded.

This is an extremely reliable paradigm, at least when my computer works. I apparently had a problem with a short in the parallel port cable between my apparatus and the computer. Only every 2-3 times the computer signaled shock did the apparatus receive and execute the command.

What I saw during my tests the next day was interesting and took a while for me to figure out. The rat was entirely nonchalant about the tone. It had been paired with a shock, but the rat did not appear worried. I placed them back in the box I had trained them in and the rat did 2 things. First, this rat immediately bit me (a totally reasonable response by the way). Secondly, the rat demonstrated it was terrified of the box used to train the tone+shock pairing.

So instead of the tone+shock association, the rat learned that the environment was unsafe and that I was unsafe.They did not learn that the tone was supposed to predict shock. Oops.

This was because the environment and myself were better predictive of the punishment (shock) than the tone I had intended.

The general case we can extrapolate from these two examples using different types of trained/conditioned responses is this: If we intend a reinforcement or punishment to be presented 100% of the time after a response, it does not take more than 1-2 mistakes to render our efforts futile.

REAL LIFE CLASSROOM EXAMPLE

Now on to our children in schools. This is a real situation from a few years back. A teacher had a student that had been placed on a behavior plan. The student was to receive 100% Planned Ignore for hitting their desk with their hands and yelling in class. I consider Planned Ignore a negative punishment since it is explicitly withholding from the student a desired stimulus they were currently receiving for the problem behavior (teacher attention). Concurrently, the child was supposed to receive 100% positive reinforcement through teacher attention whenever they raised their hands and used a soft voice to communicate.

There is usually a high implementation fidelity for about 1 day. After that, the negative punishment for hitting the desk becomes only 85% (meaning 3/20 times the kid slams the desk we forget to Planned Ignore and we give attention by yelling at the kid or staring at them with a stinkeye). The positive reinforcement usually is okay for an extra day or so, but then drops to 90% (meaning 2/20 times the student raises their hands we forget to provide positive reinforcement – as a note CRF Schedules are extremely hard to maintain. It can be draining.). The teacher is then told they need to be 100% and someone from the district straps a MotivAider on the teacher’s hip and makes them promise to reinforce the student for the target behavior every time the MotivAider reminds us.

This continues for a while. The student continues to test our patience by stubbornly refusing to respond to the plan – or so we think. We think we are doing well, but a peer taking data (usually me) notices a trend.

| Day | Fidelity (%) Problem Behavior | Fidelity (%) Target Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100% | 100% |

| 2 | 85% | 90% |

| 3 | 80% | 100% (put on MotivAider – 2 minutes) |

| 4 | 75% | 100% (put on MotivAider – 2 minutes) |

| 5 | 60% | 100% (put on MotivAider – 2 minutes) |

What we can see is that we are not doing as well as we thought we were. Basically, we are reinforcing the Problem Behavior with attention on a Variable Ratio schedule. the student does not know how many times they have to bang the desk before it happens, but they will receive reinforcement for their efforts.

We are now reinforcing the Target Behavior on a Fixed Interval, meaning we reinforce the hand raises when the MotivAider we wear – which is set for 2-5 minutes in my experience – tells us to.

Most likely the student will ignore our efforts to shape their behavior or else they will raise their hand every 2 min 1 second, and then bang the table the rest of the time because they know that they are not going to receive any reinforcements until the MotivAider goes off – and they have figured out how long that will be. So they are good for 10 seconds every 2 minutes or so, but increasingly terrible the rest of the time because being bad has a better chance of contacting teacher attention.

ARCANE FUN FACT

This is often overlooked in ABA classes and behavior plans, but it is a well-known phenomenon that if you want to make a problem behavior go away as fast as possible, you reinforce it.

If you reinforce a problem behavior 100% of the time on a continuous reinforcement schedule (CRF Schedule) until the child understands the problem behavior has a 1:1 relationship with reinforcement, then simply stop reinforcing them, cold turkey. When access to the reinforcement becomes unreliable, the behavior goes away.

To reiterate, by associating a behavior with explicit reinforcement and taking that reinforcement away, the contingencies whereupon the behavior was predicated change.

This does not apply to self-reinforcing behavior (including self-injurious behavior, sexual acting out, masturbation, etc), those are extremely hard to get rid of since the behavior itself is reinforcing to the individual.

INTERPRETATION OF STUDENT EXAMPLE

If we look above at what BF Skinner told us and what we are actually doing, we come to a troubling conclusion: We are using the most effective schedule of reinforcement for the problem behavior – Variable Ratio. This is the result of incomplete administration of negative punishment. This means that as we become increasingly less able to use Planned Ignore in response to the problem behavior, the probability the child will contact reinforcement (attention) to their problem behavior increases.

At the same time, we are using the least effective schedule of reinforcement for the target behavior – Fixed Interval because we are depending on a MotivAider to keep us honest without positive reinforcement. What we are actually doing here, is we are increasing the probability of the problem behavior occurring in a way that is highly resistant to extinction – meaning it is extremely difficult if not impossible to get rid o behavior learned this way and replace with another.

We are also increasing the probability of the problem behavior occurring in a way that is highly susceptible to extinction. In fact, and perhaps worse, Fixed Ratio schedules are susceptible to spontaneous extinction, which is the last thing we want to see in our students.

I have seen a lot of ABA therapists in practice, and have never observed a higher than 75% fidelity to their own plans. And, as I mentioned above, even computers can fail to be 100%.

This reality does not change the fact that efficacy demands absolute fidelity. The only way around this problem is to take the Lovaas approach and liberally apply extreme levels of positive punishments to every problem behavior (e.g., slapping, shocking). Here is a link to the famous 1965 Life article about the Lovaas approach that brought behavior modification underlying ABA into the mainstream – TW abuse, a lot of it. – pdf. Note the liberal application on rewards and equally abusive application of punishments.

Not to be glib. This is, in a nutshell, why ABA does not work. Applying ABA will more often strengthen the problem behavior rather than weaken it. We painstakingly train and then immediately undercut and weaken the target response.

LET’S APPLY THIS KNOWLEDGE

If we want a child to learn a skill, we teach them. This is the same with behavior. Putting a behavior on extinction is probably the most inefficient way to help a child. Teaching the alternatives by trial and error is by far more efficient and enduring.

We, as I stated in an earlier post, treat them like little adults and thank them with praise and reward when warranted – not on a schedule. This turns into a Variable Ratio schedule in practice.

-

The student never receives praise or reward without demonstrating appropriate behaviors, so they know they need to show appropriate behavior

-

This means we never use praise around or manipulative rewards to control kids, it can hijack their reward system and actually makes getting good behavior out of kids harder (link)

-

-

The student does not know when any praise or recognition for their work, but they know it is coming because you are fair in class, so they are motivated to work

-

As the year progresses, the praise and recognition the students do receive is internalized in a way that is highly resistant to extinction – and many will be able to actually learn to provide themselves reinforcement based on their behavior

-

We call this tendency to maintain good behavior despite influences that may put that behavior on extinction: Character

-

Skinner did point out that learning using a Variable Ratio schedule takes a long time and a ton of trials, but that is why it is resistant to extinction

-

Try it!

Your students will thank you.

Especially your autistic ones that are getting really tired of watching teachers fail at our own behavior plans.

Your examples and understanding of ABA are at the level of an introductory psych course for college freshman or a high school AP class. Behavior analysis is not compliance training. Behavior analyst do not ignore cognition. S-R relationship you describe is an ancient relic dropped in the 1950/60’s it is rarely used, if at all, in modern practice. ABA does work. Go tell Johns Hopkins, Emory, Mass General Hospital ABA doesn’t work, they will chuckle. Just discharged a patient whom at admission presented with severe SIB (over 2000 instances per day), broken nose, eyes popping out, skull fracture, and parents forced him to wear football gear and strapped him down to his bed 12-20 hours a day. After 8 months of ABA that kid is independent, requires no protective equipment, has a job, smiles constantly, does not hit himself, requires no medication (he was heavily heavily sedated 24 hours a day prior to ABA).

Just like medicine can go wrong, and speech, and your lawyer can screw up your case, ABA practitioners can do wrong or be ineffective. But as a whole, ABA works. And ABA is based on EAB, a rigorous science that holds itself to the same standards as medicine an physics.

Your examples here are very poor written and your reference to Skinner and others is largely incomplete misrepresentations of their work. Many of your examples are just plain wrong. Your terminology is wrong and when it’s right is used incorrectly. Your descriptions are not at all how ABA works and not how “kids learn best”. It’s like you’ve never taken a introductory course in behaviorism, experimental psychology, or applied behavior analysis, and just googled, wikipedia, and copy/pasted whatever you found on google images.

Self-injury by the way is not always automatically maintained. Extinction is not used as often as you imply. Reinforcing problem behavior on with a FR1 schedule is often done for safety reasons, not just so we can treat the behavior easier, the behavior will occur less often and with less intensity. For example, would you rather I hit myself 25 times to get your attention or one time? It also makes discriminations between contingencies easier. There is no such thing as a “reward system”. Everyone, behavior analyst, ABA person or not, uses praises and manipulates others, thats just what humans do. Have you never said “Thank you” after someone held the door open for you? That is using praise to reinforce a behavior. Are you being manipulative or hijacking someones “reward system” (this is a mentalistic construct)? ABA practitioners simply take advantage of this natural human tendency in a systematic way to produce positive outcomes with the clients they serve.

And for the love of science and good clinical etiquette USE PERSON-FIRST LANGUAGE. If I have cancer you wouldn’t call me a cancer-kid or thoes cancer people. So if I have autism why call me autistic child or say things like “try this with your autistic kids”. I am a person with autism, I am not the epitome of autism itself. I am human first my developmental/medical condition is irrelevant. Since you like Wikipedia rather than reading real scientific literature here is a wiki page on the subject: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/People-first_language

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are fundamentally wrong on most of your points. But to point out a blatant one: thinking IS a behavior. It is measurable and observable. You can measure how long someone thinks. You can see how hard they are thinking. But thinking is not a good operational definition. You would need to say thinking is defined as any time the individual is staring at his paper and furrowing his brow or some other observable behavior.

Another example of this is anxious. To be anxious is a behavior but it is not observable. What IS observable, however, are things like tapping fett biting nails, biting inside of cheeks. While we may not know if a person is anxious, we can certainly tell if they are exhibiting the afore mentioned behaviors, and can assume that they are anxious.

LikeLike

I am happy you are offering your opinion. But I will point out from a behavior analytic perspective, what you suggest as observing anxiety or thinking is nothing id the sort. You cannot pick and choose when to use strict behavioral definitions and when you can apply cognitive assumptions.

You are not observing thinking if you observe furrowed brows or staring. You are observing furrowed brows and/or staring at paper. This can happen for a number of reasons having nothign to do with thinking — like a kid could be wasting time or has had furrowed brows rewarded in the past. Same with anxiety attributed behaviors. They are behaviors, not anxiety

LikeLike

If a behavior analyst with a certain philosophical background may make a comment. Anxiety is a label that can only be described as a collection of behavior. Linguistic reification is a common source of argument between educated people. From a neuroscience perspective, what we call thinking can be measured as patterns of brain activity. Behavior analysis as a science has made no declaration against incorporating the technology of neuroscience, however, functional assessment are more less cost restrictive. Well designed ABA interventions are, by definition, effective technological applications of behavioral control. For a professional, there is no problem with highlighting a case where more effective control is possible. In practice, ignorance of the science can limit the applied skills of a practitioner to control behavior. The claim that ABA doesn’t work is all over the internet, however, the control of behavior is there, regardless of the source. And as a proliferation of the literature of counter control (as Skinner might write) continues, it strikes some of those practitioners in the field that the effects of designed control might inappropriately noticeable or powerful for the context. There are indeed times where interventions might best be focused on peers, parents, and teachers rather than the student. As the author points out, tracking schedules is very difficult outside the lab.

LikeLike

“I consider ABA to be compliance training and I have grave concerns regarding the long-term consequences of teaching disabled youth that compliance with instructions from people in authority is more important than their own instincts”

You do understand, that ABA is in most situations teaching children with disabilities, specifically autism, to communicate with words, sign language or PECS, how to eat, and sometimes how not to hit their heads on floors or bite themselves. We are not teaching them to get into vans with strangers. Sometimes we teach our clients to say their parents names or where they live in case they get lost. They don’t comply with these programs because we “have authority” (although this is not atypical in our society in general, ahem, following laws, etc.), but because we “pair” with them, meaning we associate ourselves with reinforcement in the form of social praise and fun interaction and they cooperate in the learning because they want to.

Do you believe that a person hitting their head on the floor is “instinctual”? In most situations, I believe it’s learned unless an underlying medical condition exists.

LikeLike

I think it is important to have the conversation that perhaps we can do better. Frankly I get a bit tired of ABA defenders dismissing what many families and educators have longed complained about. The “shields” they put up of prestigious institutions that ABA as the only proven treatment is very distressing, because in essence they are saying “case closed”. Look no further. I find this attitude dangerous.

What many of us see is that over the years the children become quite prompt dependent and (yes dare I say it) compliant, and lacking in sophisticated judgement. I’m not saying that ABA doesn’t “work” in what its focus is; having the child learn discrete static skills, or training away from self-injurious or socially stigmatizing behaviors. However, the reason ABA will always fall short is that it is limited in a very narrow range of learning. There is no ABA program that will prepare a child to merge into playground play during recess where the conditions, criteria, and characters are in constant flux. Where rules change and decisions are made in real time totally dependent on the novelty of each and every unique moment. That living life has no predetermined “right answer” or script. If we only focus on behavior our kids will learn “stuff”, but they will have a terrible time learning “life”. Life, in all of its uncertainty and unpredictability. Where there are no clear answers or solutions to make. Where what works one day may not work the next, etc. Where life if about discovering, “who am I” as a person. It explains why a child with autism who graduates high school and perhaps even college, fails to acquire meaningful employment or live outside the family home. Fortunately, more study is being allocated to adults with autism. What is interesting is it seems that all this effort in EBP’s doesn’t yield too much. For example in one study 80% of adults with autism who graduate from college are either underemployed or unemployed; most likely forever dependent on their parents, or government subsidies.

I also disagree that the scope of human experience, learning, thinking, is strictly behavior. The idea that we only “do things” for some kind of reward or the avoidance of punishment is misleading. To say that the whole depth and dimension of human experience, connection, cooperation, and collaboration can only be measured in behavioral terms is so limiting and bereft of all imagination I sometimes feel ABA types are living on another planet.

What we need to shoot for is to help children learn as all children have learned since humans walked the earth. How a child learns today is no different than 10,000 years ago. Human development has the answers. We were born dynamic thinkers and problems solvers. We were born learning to adapt, experiment, assess our solutions and evaluate our choices and apply them to our future thinking. We see evidence of this in infants.

So full disclosure, I am a parent of a now 17 year old boy with autism. Diagnosed as moderate severity non-verbal. I never did ABA but did Relationship Development Intervention® (RDI) solely. RDI recognizes human development. It recognizes that autism is the result of a child who is unable to successfully and meaningfully be a mental apprentice to the parent. For parents lay the neural network the allows the child to experience what it means to be human. I learned how to guide him in ways that mirror typical development. And my son learned to think and problem solve in dynamic ways – dynamic intelligence, not static, is what allows for authentic independence to take place.

I think we need to “raise the bar” for so many kids with autism. They deserve to experience the joy and empowerment that comes in being able to solve life’s problems no matter what comes. That solutions may not work out as expected, and they may not have the answers, but they believe that they can ultimately guide themselves. This is what growing-up is all about, Unfortunately ABA is just not set up to deliver this. Parents are recognizing that while ABA says it is an effective “treatment” for autism we already know that “something” quite profound is missing. And telling us that we don’t “understand” will not make that feeling go away.

LikeLike

This is a really interesting take on the issue, but I must say I am sad your experience has taught you that FR schedules are always used for skill acquisition and intermittent reinforcement for problem behaviors.

All my clients have varied ratio or interval schedules of reinforcement. We do not solely extinguish problem behavior, but we use differential reinforcement to make sure we are actively teaching replacement skills.

LikeLike

No, my experience has taught me that both are most often used inappropriately. The point is not what schedule is selected, it is that they are almost always improperly executed and there are implications for IR with problem behaviors, even when replacement behaviors are being concurrently taught.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Autism Candles.

LikeLike

Hello there! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that would be ok. I’m definitely enjoying your blog and look forward to new posts.

LikeLike