An Education Aside

So I have been thinking a lot about behavior and why I am able to effect significant change in a classroom when people purportedly more qualified than myself fail. I have come to the conclusion that my success is entirely the approach I take. This method was learned from my mother and from CBTU (now the Carmen B. Pingree Autism Center for Learning) in the 1980s. When my mom worked there, and my brother attended, CBTU was coming up with a Behavioral Therapy for autistic and otherwise disabled kids that was disconnected from what they called, “The Lovaas Method” at the time and we call Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) today. Their CBT was intentionally a deviation from ABA, which they described as far too ready to apply positive punishment to mold behavior instead of teaching kids explicitly how to act in school.

The take home point for this post is going to be that all kids think. All the time. Kids try to figure out stuff – often things they are developmentally incapable of understanding. Problem behaviors happen because they cannot understand something or they are unable to process some incoming stimulus. The sooner we realize that little Down Syndrome boy, the nonverbal autistic girl, the boy with cerebral palsy or Angelman Syndrome in a wheelchair are sitting there thinking, the better off we are all going to be. If you take the time to look in the eyes of a lot of these kids you see the gears are grinding and the kids are exploring the environment. They are planning. They are scheming. They are learning. They are looking for fun to be had and adventures to embark on.

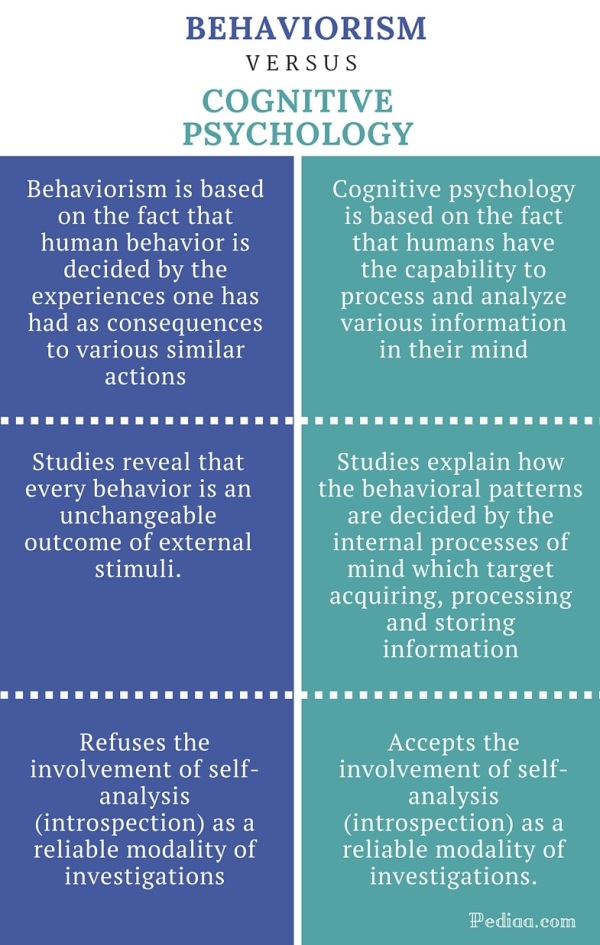

Behaviorism vs. Cognitive Neuroscience

Before I dive into my point in the next section, I need to explain where my approach comes from. That means I need to define Behaviorism and Cognition, so the differences are apparent.

The easiest to understand definitions from as cursory google search was located here:

Cognitive psychology

Cognitive psychology assumes that humans have the capacity to process and organize information in their mind. It is concerned less with visible behavior and more with the thought processes behind it. Cognitive psychology tries to understand concepts such as memory and decision making.

Behaviorism

Behaviorism only concerns itself with the behavior that can be observed. It assumes that we learn by associating certain events with certain consequences, and will behave in the way with the most desirable consequences. It also assumes that when events happen together, they become associated and either event will have the same response. It does not note any difference between animal behavior and human behavior.

Both branches of psychology attempt to explain human behavior. However, they are both theories have been replaced by other approaches (such as cognitive behaviorism – which takes the best of both theories – and social psychology- which looks at how our interactions with others shape our behavior).

[…]

Comparing Cognitive and Behaviorist Psychology

The cognitive approach revolves around the concept of understanding why people act in specific ways requires that we understand the internal processes of how the mind works. Cognitive psychology is specialized branch of psychology involving the study of mental processes people use daily when thinking, perceiving, remembering, and learning. The core focus of cognitive psychology is on the process of people acquiring, processing, and storing information.

The practical applications for cognitive research include improving memory, increasing decision-making accuracy, and structuring curricula to enhance learning. Cognitive psychology is associated with related disciplines such as neuroscience, philosophy, linguistics, and instructional design. Researchers in cognitive psychology uses scientific research methods to study mental processes and does not rely on subjective perceptions.

From 1950 and 1970, there was a shift away cognitive approach and movement towards behavioral psychology that focuses on topics such as attention, memory, and problem-solving. In 1967, American psychologist Ulric Neisser described his approach in his book Cognitive Psychology. Neisser states that cognition involves “all processes by which the sensory input is transformed, reduced, elaborated, stored, recovered, and used. It is concerned with these processes even when they operate in the absence of relevant stimulation, as in images and hallucinations… Given such a sweeping definition, it is apparent that cognition is involved in everything a human being might possibly do; that every psychological phenomenon is a cognitive phenomenon.”

The behaviorist approach emphasizes observable external behaviors rather than the internal state of the mental processing of information. Key concepts of behavioral psychology includes conditioning, reinforcement, and punishment. The basis of behavioral psychology suggests that all behaviors are learned through associations as demonstrated by physiologist Ivan Pavlov, who proved that dogs could be conditioned to salivate when hearing the sound of a bell. This process became known as classical conditioning and has became a fundamental part of behavioral psychology.

To take this down to brass tacks, Behaviorism focuses on things that we do – outward behavior. ABA tends to describe this as the “dead man test.” Behavior = anything that we can observe a living person doing that a dead person cannot do. A classic example is that putting on clothing is a behavior; however, wearing clothes is not. A dead person cannot put clothing on, but they can passively wear clothes. As such, Behaviorism/ABA focuses on how we can modify the external world to change behavior, with behavior as a recorded output. Based on these definitions and relevant to this post, “thinking” does not qualify as a behavior, because the actual act of thinking is not outwardly quantifiable by an observer and thus fails the dead man test.

Cognition focuses on thought processes. How information is processed. So the outward behavior is less important than the thoughts/mental processing that underlies the action. This means that any cognitive therapy focuses on helping a person change behavior by focusing on helping them to understand or alter their internal thought processes. Data are recorded on not only the behavior but also by debriefing the person on what they were thinking, feeling, reacting to, etc. before, and during the moment the behavior occurred.

Both of these are flawed in that they ignore critical data the other focuses on. I fall under the category of cognitive behaviorism. I focus on how the environment results in behavioral change, but always through the lens that the agent is thinking about what to do, not just working on a stimulus-response chain. To hybridize the above definitions, I focus on how the environment changes out thought processes, leading to alterations in our behavioral choices. I then add to this a clinical neuropsychology approach in that I believe brain structure and function drive behavior. So if there are alterations to brain functions, then any behavior or thought processes are interpreted differently.

What is my model

My working model is almost ludicrously simple. It derives from cognitive behaviorism, which is the theory underlying Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. CBT has a strong emphasis on the assumption that misbehavior often occurs because the child (or young adult) does not know how to be well behaved or have never been taught there is a reason to not show maladaptive behaviors (i.e., a skills deficit). So misbehavior happens because of a lack of education. The child is not making poor choices, they do not yet understand they have a choice. They are just doing. I focus on ability gaps (knowing how to behave) because I have found the work of Ross Greene to be very influential in my practice. I started my approach before reading The Explosive Child and Lost At School, but these books shaped my methods into more of a coherent process than one being made up on the fly from scratch every time. Dave Altier developed a democratic classroom model that extended these ideas to entire classes, but that is beyond the scope of this post.

When there is the necessity to engage in behavior modification, which in my opinion is only when the intellectual function of a child is 2-4 years old, I use what I learned as a rat researcher. I have covered that here, but in précis: repeated, consistent reward changes behavior, fear and aversive consequences do not. Punishment breeds violence and rebellion. So I don’t use those methods. I praise. I reward. I give tokens. I tickle. I cuddle. I play. Kids grow.

A unique aspect of my approach is that, if a student is in kindergarten or older, I rarely use external, tangible, or edible rewards. I provide access to opportunities, access to my attention and time, or some form of social reinforcement. In that sense, I am a definitely an adherent to Alfie Kohn’s theory that we often create prompt dependence and harm our children by liberally applied and excessive, rather than the thoughtful and careful application of reinforcement strategies.

In a basic, behaviorist interpretation, in the absence of information, kids tend to be engaging in behavior to contact reward based solely on a history of that behavior contacting or accessing reward. However, this can change rather quickly with some knowledge. In a cognitive sense, they do not think before they act (or lack executive function).

My general approach to helping a student prone to behavioral episodes is as follows:

- I spend 2-3 days watching the student behavior so I can ascertain what the people around the student are doing before, during, and after the problem behavior. Sometimes I use an A-B-C chart from my Behavior First Aid Kit and sometimes I just look for broad patterns when they are obvious and don’t require careful data collection to characterize.

- I talk to the adults in the room to change their behavior to see if changing the environment is sufficient to change the child’s behavior (this is totally using the strength of ABA by changing the environment – the behavior of the adults – to see if the student responds favorably and saves us all a whole lot of work). Then I watch for 2-3 days doing a fidelity check on the adults.

- I set a time to talk with the student privately so they and I can “make a deal.” In this way, I am very similar to Ross Greene and the CPS model. I have a series of conversations with the student so they can identify the problem or challenge they are having and brainstorm some potential solutions.

- I provide the student with some datasheets THEY can use to keep track of their behavior. I am a huge proponent of self-management strategies as a primary method of effecting behavior change (here). I let the student decide what they will EARN when they reach a goal (no prizes, we earn things with good, prosocial behavior)

- I model to the student how to fill out the sheet using myself as a positive and negative example

- The student and I both fill out the form based on their timer beeping, and we compare answers at the end of the day and discuss differences

- When the student and I agree, and the student KNOWS I will not punish their honesty, I cut them loose on their data sheet and behavioral plan

- Lather, Rinse, Repeat as changes need to be made – always focusing on letting the student take the reigns as soon as they are ready

I also take care to do the following throughout the process:

- Throughout the entire process, I engage actively in a differential reinforcement of incompatible behavior (DRI), which means I reward behaviors that CANNOT occur at the same time as the problem behavior. This results in VERY high levels of reward or praise. This also has the added benefit that when I tell them, “I cannot give you [X]” or “I have to walk away to work with Bobby now because he is ready to work” because they are making unexpected choices, the loss is clear and conspicuous.

- When a student decides to behave and then look over to me for reinforcement, I tell them they need to go to whatever they are supposed to be doing, and I will come talk to them when I am done with what I am doing. They have to wait. I consider myself a commodity that all students have an equal right to, and I am not going to deprive a student of my attention because another one decided to start acting right after misbehaving.

- I also, to prevent power struggles, when a student engages in problem behavior during school work, I remove access to the school work until the student shows they are ready to get back to work – and without fail I notify them what they have to do to get their assignment back. This also means my primary punishment is boredom or lack of access to “stuff” to do. I started this because it prevented things getting thrown at other students, and it just happened to work out that it is an effective strategy (here is some research).

- If a student uses a tantrum or tries to simulate a meltdown (not having a meltdown but trying to put on a huge show to contact escape), or otherwise makes a fuss to avoid work, I take the work away and let them know when they are done they get it back. But they have to complete as much of their assignment as their friends did before they get fun activities. I do this with a very clinical, stony faced expression and do not respond or punish the student if they hit me at that point, it is just another bad choice, but they are reacting to a statement, not exhibiting behavior that needs addressing. This is the same if “anxiety” or “depression” are used as excuses. (Note, I say this as an absolute because by experience – both personal and professional – I can tell true anxiety and depression from malingering and excuses. Same goes for distinguishing fake tantrum crying from a true meltdown).

- If a student has a true anxiety disorder, we adapt the assignment to drop the anxiety levels down. Same for depression to avoid learned helplessness. If a student has a meltdown, then I evaluate what the trigger was and we work on that in the future. A student having a meltdown means I change the day to address academics later, once they are back from crisis. Usually, I have them complete 1-2 questions from what they needed to do and then move on with the new task. That way they can be reinforced for working on all assignments, but we do not punish the presence of a meltdown because that only leads to learned helplessness.

- Explosive and/or dangerous behaviors are dealt with using MANDT de-escalation and physical intervention procedures as necessary. Every time I use these procedures I start a functional communication training with the student and all other plans get put on hold (here).

- If a student used violence to escape work, then they become very well acquainted with me, more so than they would like. We go into an empty room devoid of any stimulus other than writing utensils and assignment materials. And we work. I shrug off any attempts at violence and keep the academic pressure on until the student realized they are not going to get reinforced for violence. If they ask for a break, I give it. If they ask for space, I give it. If they tear up their paper, I tape it together, and we get to work.

- When a student has difficulty in emotional recognition, self-regulation, or any other socio-emotional difficulty we start a brief study of either Social Thinking or Zones of Regulation depending on which program best fits the student’s needs.

I know some may say that this is all fine and good, but what about my severe kid, nonverbal kid, Down’s kid, violent autistic kid, etc. They are too low for this to possibly work!

Well, I beg to differ. Experience has taught me that often times these so-called lower functioning kids are actually more attuned to my approach than some higher functioning kids.

So, my recommendation is to do the exact same thing as you would do for a highly verbal, naughty, typical kid. I have used this method for severely disabled students that were nonverbal all the way up to Genius-level IQ twice exceptional autistic students that had learned how to manipulate situations to get power and control. Empowering kids works. Seems to me that sometimes handing over power is the only thing that does work with the truly tough kids.

Like any teaching, we have to differentiate it to the level of the student. If they are nonverbal, then adapt and use their communication modes. If they use eye gaze, then develop choices and iterate through options until the student signals approval. If the student is a smarty-pants, leave them to write their own plan. I have even had a student write a literal contract because they did not believe I would be honest. So I had him write the contract, and another teacher came in and notarized our signatures.

I have also had a few autistic students that found mentally taking another’s perspective quite difficult. We had to make a video model with the things this student was doing happening TO HIM. It was always acting, and no one ever made this student uncomfortable, in fact, they loved making the video. Watching their face when they saw someone “hurting” them or “being mean” or “bullying” them was a revelation. They knew they did the exact things they were seeing. But watching themselves “fall victim” was enough for them to demand immediate punishment (which I refused to give) and then they proposed a series of draconian requirements for them to repay others. I walked them back to just changing their behavior and apologizing to others they may have hurt. I point this all out to suggest that there is NO ONE so disabled or so socially inappropriate that they cannot respond favorably to this type of system.

Most kids will just be happy to be in control of something. Often they forget to misbehave because they are too busy marking themselves down as not being naughty.

What does my intervention look like

I will start with the youngest ages I work with, Kindergarten. I start at this age to illustrate a point. That point is that you can teach kindergarteners how to behave, even disabled kindergarteners.

My example is going to be a student I worked with a few years back. This student, who I will call Johnny, was challenging. Before I came into the classroom, Johnny had bloodied the mouths of 3 paraeducators and had become a sniper with wooden blocks, being able to hit his target from across a classroom. Johnny also had taken to bolting out of the classroom for two purposes: to run into a certain classroom to either break objects or bang the blade of a large paper cutter up and down; or else he would run into a locking bathroom on the other side of the school and barricade himself in. This was a daily occurrence, and by daily I mean this student was being restrained in place to do his work, had his hand held in a choke to walk down the hall. In other words, he was a handful and at the edge of being “disinvited” as one teacher put it, from attending school in this classroom.

When I came in, I followed the school plan for the first two weeks. These were ABA-derived plans designed by a district employed BCBA. Here are the particulars:

- When this student misbehaved the staff were to engage in planned ignore and to praise the replacement behavior (Differential Reinforcement of Other Behavior – DRO)

- When this student misbehaved the staff were to engage in proximity praise, meaning peers that are behaving were to receive reward

- When this student attempted an elopement, they were to be touch prompted (e.g., forced physical guidance using MANDT procedures) into the room and placed in seclusionary time out in a Time Out Booth (a punishment contingency)

- When this student attacked another student or teacher, they were to be placed in seclusionary time out in a Time Out Booth (a punishment contingency)

This plan was an utter and complete failure. Analyses of the function of the behavior did indicate attention seeking, and the BCBA programmed accordingly. The problem with that was this student was not acting for attention in the classroom. Not one bit. They actually preferred to be in a spandex body sock and under a bean bag where no one could see them. When it came to the hallway and eloping, that was 100% for attention. The student wanted to be chased and wanted to get the goat of the teacher whose items he would break.

When it was clear the ABA behavioral intervention plan failed (based on my fidelity data and a district advisor’s data the plan was carried out with >95% fidelity), I was tasked with developing a new plan.

Here it is (in order).

- This student worked 1:1 with me for 2 days. As we did work, I explained what was going to happen for the rest of the week and the next week

- I told him his behavior was unexpected and I was going to help him to express his needs in a way that was not going to get him in trouble or scare teachers/students

- I asked him for options that he could do instead that would contact reinforcement rather than punishment

- For the next two days, I walked Johnny through his options. If he wanted to throw things, he would tell me. When he wanted to punch or kick., he would tell me. When he wanted to run, he would tell me.

- After that, I worked with Johnny on the Social Thinking and Zones of Regulation curriculum while still working on earlier steps in the process.

So how did it go?

Week 1 was less than a party. I was cussed out nearly constantly. Johnny did not like having our conversations. He knew I was going to stop him from misbehaving. I know this because he screamed at me many times, “I don’t want to tell you. I want school to be done. I hate you. I will hurt you. You don’t let me have fun”. During the last statement, he would act like he was cocking a shotgun and shoot it at me. He attempted to elope 8-10 times. He tried repeatedly to grab blocks and throw them at my head. He tried to punch me in the mouth … a lot.

Each time I calmly, and without showing any emotional response, stopped the behavior. I said nothing. I just made sure the behaviors did not happen. I did not want to give any potential fuel to the fire behind any behaviors. So I didn’t, I only frustrated the attempts. When Johnny bolted and I was unable to stop them, I sat in the hall by the door furthest away from where Johnny wanted to run and watched (and texted the teacher down the hall to shut her door). When he locked himself in the bathroom I waited on him to get bored. It took all of 2 minutes and he came back and apologized.

Starting the second week I started to get my pants or shirt pulled on and a tiny whisper saying, “I am going to be bad”. I leaned down to eye level and whispered back, “What are you going to do instead”. This was often met with either a hug or else the student would run away and dive under a bean bag or lunge toward the body sock he preferred.

This was the extent of behavior modification I engaged in. Behavioral change only took a week. And I assiduously avoided using any kind of behaviorist interventions as they had proven entirely ineffective before and only made this student’s behavior exacerbate.

Now, as to the Social Thinking curriculum, that was the hard part. Kindergarteners are not typically ready for social skills lessoself-reflectionlection sheets, but I felt this student needed to know how they were making others feel. This was hard for Johnny, but he understood with time that he was scaring people. It was a game to him, but teachers and other kids were scared.

He never wanted to scare them or make them feel bad. He was having fun like he saw in movies (His favorite movie of all time was Kill Bill, which might explain the tendencies toward violent play). Once he understood that he was being naughty, he changed his behavior. He was still naughty, but it was not using such grand gestures as before, but rather it was work avoidance, hiding in the classroom, typical kindergartener silliness.

Fast forward to summer school. Johnny and his class are walking down the hallway and he sees me. He stops, looks me in the eye, put his hands behind his back and says, “Hello Mr. Ryan, how are you today? I am still being good!” and he walked away with his class. The teachers just stopped and stared at me. They could not believe that a) he could speak as he was selective mute other than screaming, and b) that he reported he was being good without me asking. I let them know that we had developed a rapport and that he trusted me, and thus valued my opinion and knew I valued his.

My point with this example is that Johnny did not need to have his behavior modified. He needed to be taught how to behave. To be given the tools necessary to understand how he was impacting others. The behaviorist method only emboldened him. A more cognitive approach (that of training the mind in understanding rather than consequences), solved his issues in virtually no time flat.

Now to more, quick examples

My mother uses the same methods that I do. She has recounted some examples that are illustrative across a number of behaviors:

- She had a student that was a Brony and would bring his My Little Pony toys everywhere. It was clearly turning into an autism-like obsession that was getting in the way of his daily function. Importantly, it is not the brony or the dolls that are the problem. Those are fine, it was the fact that this student was beginning to act like a preschooler with these ponies. So it was clearly inappropriate and not just a benign interest. Since it was becoming a problem, my mother pulled this student aside and told him that My Little Pony was for home. When he was in his room he was 100% allowed to enjoy My Little Pony and his toys. But when he was at school, he had to act like a middle school student and not younger than he is. She then walked away. She later found out that this student had put his toys away and told his mother that he was growing up and getting too big for those toys now.

- She had a student that was running out in the field every recess doing a very happy autism stimmy flappy dance. He also was very sad that he did not have any friends of people that would play with him. My mother pulled him aside and asked him if he knew what he looked like when he was pacing and stimming out at recess. He thought about it for a minute and walked away. He then changed his behavior. He started trying to interact with peers at recess and not just stimming all recess. He did not realize how his behavior was affecting others. As soon as he did, he effected a change.

- She had a student that would swear. And he was good at it. He had come from another state that had taught him to just write the words instead. So she was hearing the words and watching this kid write them down. In this case my mother had a number of conversations with this student and the swearing was going down, but it was a peer tutor who finally put the coup de grace on the language. As was reported to my mother by this girl, at recess this kid was cursing, and the girl pulled him aside and told him in no uncertain terms that at that school they do not talk like that. And that she would not be able to be his friend if he swore like he was. He stopped right then. he even asked my mother if she knew they did not swear at that school. Mom responded something along the lines of “is that right?” and let the student stew. He actually did not know he was not allowed to swear and that he was repelling potential friends. His behavior changed on a dime as soon as he found that out.

- My mother had a student that was behaving and refusing to do work in class. Finally, in a moment of either exasperation or inspiration, mom pulled the kid aside and showed him that the answers to the worksheet were in the book. IT HAD NEVER ONCE EVEN OCCURRED TO HIM that the answers were in the book. To this kid, school had to feel like a bunch of mean teachers being rude and unfair. Armed with knowledge, the student behavior faded away since he now had the skills and knowledge necessary to succeed at school and not feel inadequate.

Some of my examples:

- A student was running up and down the hallways making a horrible noise akin to a howler monkey every day. They also were constantly standing up in class and making a screaming noise. I asked this student why they were making that noise. They said they did not know. I asked if they knew how others felt when they heard it and the student said they did not know. So I initiated a conversation about voice volume in the halls and echoing and how that hurts people’s ears. We discussed how this student had to wear noise canceling headphones the year prior because they could not handle excessive noise. When the student heard this he asked, “Am I hurting people?”. I asked him what he thought and he was quiet. The next day his volume was greatly reduced, and by the end of the week, he had stopped yelling altogether.

- A student was constantly reporting on everyone in the class when they were out at recess. The other students were startling to bully this student and isolate him on the playground and in class. When this student came to class one day they kicked over a desk, stood on it, and notified everyone in the class that they were going to die for crossing him. This continued for a week and escalated, This student started lashing out at the other students by throwing items, kicking them, and overturning his desk aggressively. When I was called in the classroom had instituted a plan to proximity praise systems for good behavior, and set up a DRO system whereby they rewarded behaviors that were “good” and simultaneously punished the behaviors this student was displaying. This had only served to make things worse. The student had taken to swearing at teachers and threatening to kill them in their sleep. I had some discussions with the student. I asked for why they were showing their behavior. They said it was because they were angry and they hate themselves when they are angry. So they were acting like they felt. He wanted to get kicked out of school and he wanted to get arrested. We talked about emotions and how they are okay. Even anger. If he has a hard time controlling himself when angry, that is okay. We can practice. Oddly enough, at that point, he walked back into class, apologized to everyone, and told them his behavior would change. I did not ask him to do this. He did not even warn me he was going to do it before he did. He would stop tattling, and he would stop hurting and scaring people. And he kept his promise. He and I worked for the rest of that year and the next on managing emotions and learning how to just live with being angry. I ended up buying him a copy of the Zones of Regulation so he could have it and work with his mom and dad over the summer.

- A student with poorly developed social skills that everyone thought was autistic but wasn’t started mainstreaming. Unfortunately, as he had been in self-contained special education classes for all of his schoolings, he was a bit naive when it came to navigating the elementary school social situation. He got in trouble for the following because kids were doing it and he was working to fit in and be friends: He peed in the sink instead of the toilet in the bathrooms. He peed on the floor rather than the toilet (and I mean nowhere near the toilet stall or urinal). He googled some rather creative porn searched on the school computers. The general education teacher asked me what to do with him. The special ed teacher whose class I took him out of punished him severely, but the punishments were making the adults lives a living hell rather than this student (he had Tourette’s and they were taking away recess, so he was not able to run out his excess energy. So he was break-dancing all afternoon in class). I explained the method of educating him as if he did not actually know any better than what he was doing to the general education teacher and the principal. The principal was already on board because, like me, she saw this all as rather hilarious and benign given the behavior was not actually hurting anyone. So the principal and the teacher explained to him in excruciating detail what was expected of him and how his behavior was deviating from those expectations. He apologized and did not act out like that again. He came up to me the next time I was in the school and asked me why his friends wanted him to do things that would get him in trouble. I told him it was because they thought it was hilarious to see someone do those things, and that they wanted to do them but did not dare because they would get caught. I even told him that it was because he had a disability that they were teasing him to get him to do this things. He asked if they would still be his friends if he made better decisions and I said that some would and some would not. But the ones that stayed his friends would be great friends for years. The other ones just wanted to see him get in trouble. He thanked me for my honesty and told me he was going to be a better kid from that point on and not (and I quote) “be anyone’s little bitch” from that point on. And, he wasn’t.

- My final example is a boy with fragile X syndrome I worked with. He started the year getting in trouble by coming to school 2 hours early and standing in the lunch room flipping off the teachers and saying crude things to girls in Spanish. He also would wait until the opportunity arose to inflict maximal chaos and would sweep everything off tables in the lunch room during breakfast. Then he would run a way and laugh. He also would randomly punch people for what we could tell was no specific reason. He also would eat his decidable books and any materials the teacher gave him, laminated or not, entire pencils, erasers, and even the fabric eraser. He was a mess to say the least. He also was selective mute so it was hard to hold him to account since he was unable to communicate when in trouble and would just stare. So when I got involved it was tough. In this case I did a lot of talking. I told him how his actions made other people feel. I let him know that since he was acting in a very unexpected way, others did not know how to act, so they got very anxious and scared of him. This was not conducive to having friends or being able to stay in school with peers rather than being moved into a classroom with only an adult and school work. He did not like the idea of not being near friends. So we worked on a plan. I gave him time and space to be able to speak so he could communicate his ideas to me and I would not make a big deal of his selective mutism. I asked him what he could do when he felt like being naughty and he said, “be naughty?” I asked how he would feel if people knocked his breakfast away and he said, ‘I hit them”. Figure int that was a start, I ran with it and informed him that the kids did not hit him because they did not want to get in trouble. He went a bit ashen and asked if I was being honest. I said yes. He thought he was having fun and they were too. No one was hitting him, so it had to be good fun, right? His behavior did not stop immediately, but he allowed me to help him shape his behavior toward more appropriate behaviors. Like a number of other students, his naughty behaviors went from violent and aggressive (and eating his school work in this case) to just normal age-appropriate naughty. In this case he started to talk in class and hide things from the teacher to get her attention.

Conclusion

It is my resolute belief that all students can learn to control their behavior. They are not slaves to stimulus-response contingencies or to “dark thoughts”, anxieties, or depression. As teachers and therapists it is our responsibility to help disabled children and adults to navigate the world. How to be social. How to be appropriate. How to get what we want. How to stay out of jail.

My approach is simple. Empower the student. Use ABA-inspired data collection methods to collect data on behaviors, but then look past the surface behavior and identify what thought processes underlying the poor choices. Then help the child overcome those processes by trial and error learning in a safe and loving environment.

Simple. And sensitive. The students will feel and respond to your compassion. And honest compassion breeds trust.

4 thoughts on “Kids Think: Behaviorism Will Fail Until It Accepts This Fact”